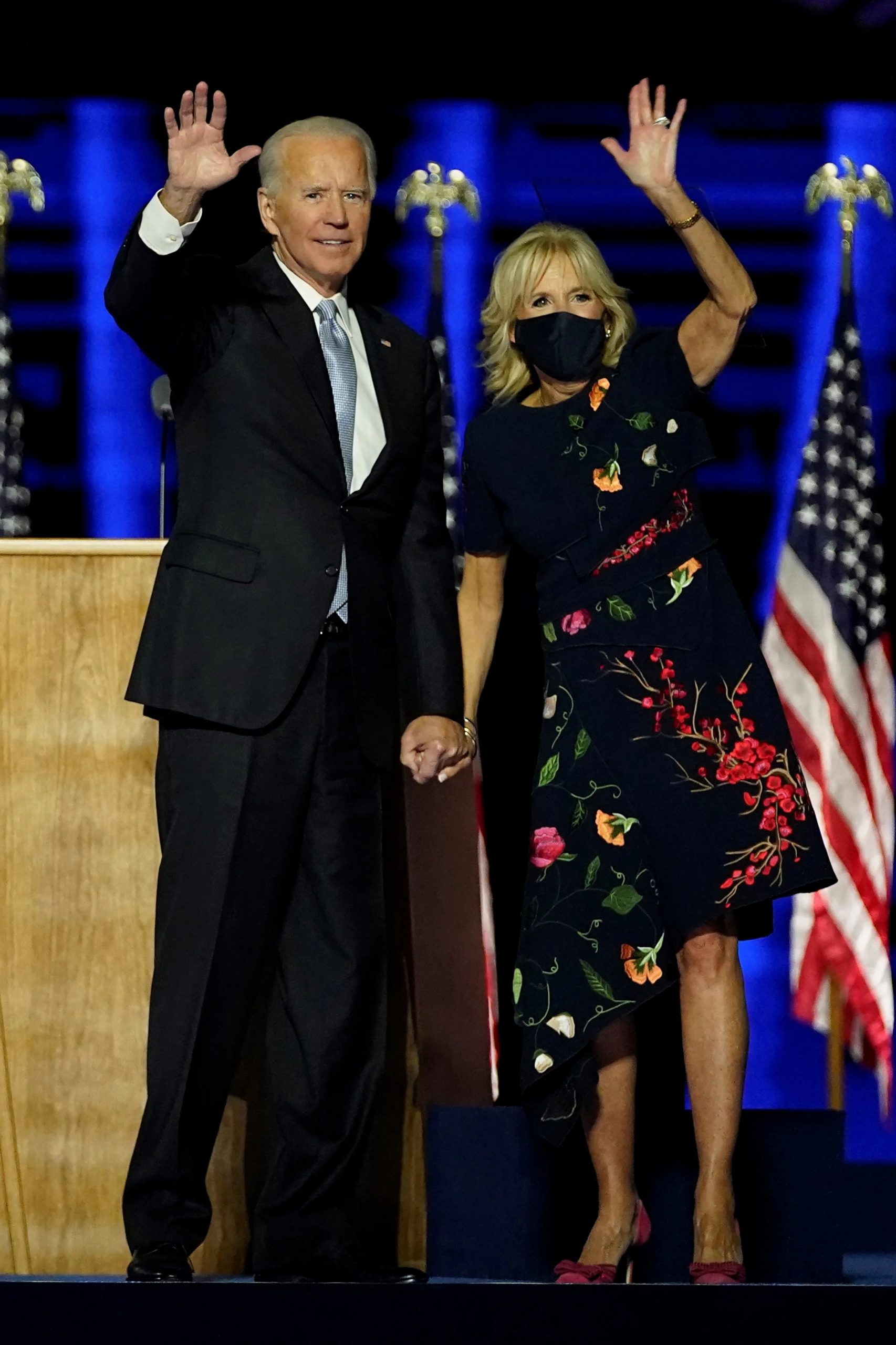

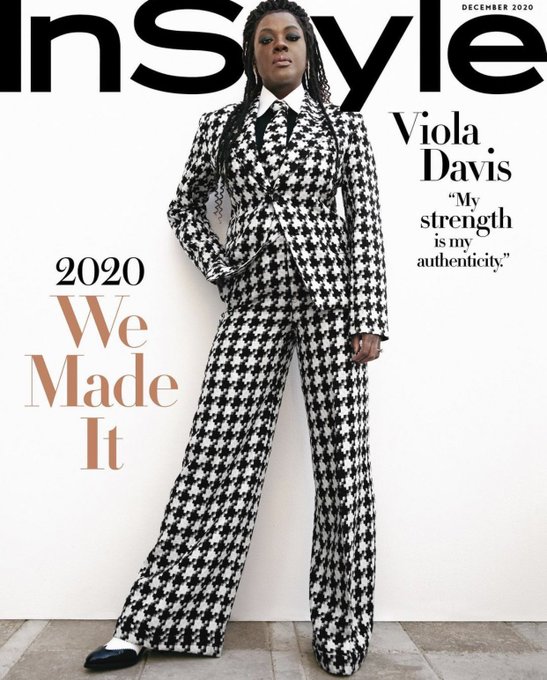

Viola Davis Covers InStyle Magazine December 2020

Laura Brown: Viola Davis! How are you?

Viola Davis: I’m doing OK. How are you?

LB: Totally fine, but it’s, like, at the end of each day right now, you go, “Yeah, I did it!”

VD: Oh, yes, I know, and I haven’t had a cocktail yet today, but, you know… [laughs] We have a new puppy, Bailey, too. She is so precious and fluffy. She’s healing my broken, cold heart.

LB: There is a word that comes to mind when I think about you: “command.” I just watched Ma Rainey, and you’re playing a character who has nothing but command. What attracted you to the role?

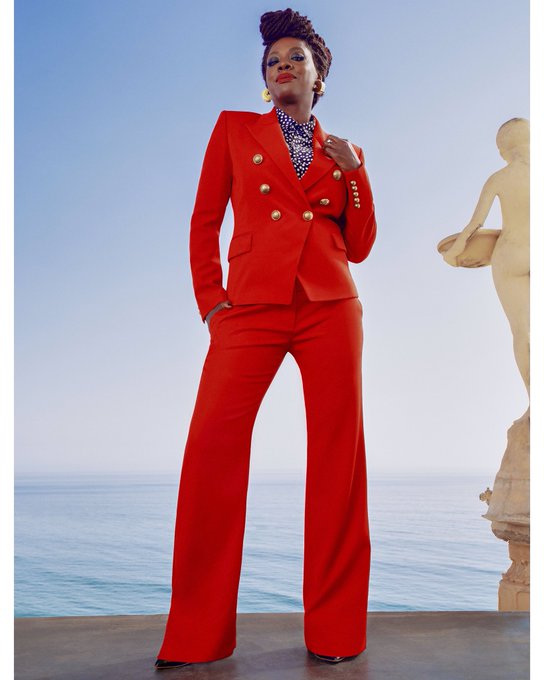

VD: Everything attracted me to Ma Rainey, especially the idea that I didn’t feel I could play her. But she also really reminds me of the women I grew up with, all my aunties and relatives, the people who were bigger in stature whom I saw as so beautiful. They never questioned their worth. They had the full makeup, the earrings, the Afros, the wide-leg pants. In white American culture, the idea of classic beauty and confidence has always been associated with extreme thinness, but not in my culture. In the African-American culture, we are in command of our bodies. There’s an unapologetic way that we approach clothing. Even in the way Ma Rainey’s breasts were hanging out. At first I was like, “Should I pull my dress up and be more modest?” But I had to channel Ma, and she wouldn’t do that. Neither did my relatives.

LB: Coming up in fashion, I’ve always questioned the fetishization of skinny, deprived-looking women. In Black culture, you so often see the opposite and the ownership of it.

VD: Absolutely. I think the whole notion of ownership in womanhood has to deal with how we look. And it’s only until you reach about my age, 55, that you have the powerful understanding that ownership is about owning yourself. It’s owning your failures, owning your insecurities, and understanding that it’s a part of life. A lot of times we have those hiccups in the road, and we spend an awful amount of time — years — trying to sweep them under the rug instead of understanding that they’re a part of the joy.

LB: Do you remember the first time you felt ownership as a performer?

VD: That’s hard because imposter syndrome is a huge part of an artist’s life. With social media, you’re not supposed to say that; you’re supposed to say you’re the boss. But when you’re an artist, you always feel like you can do better. I once did a workshop production of King Lear at the Public Theater — George C. Wolfe [who directed Ma Rainey] was the director. I was playing a lesbian who was pretending to be a man. On the first day of rehearsal, I took my nail polish off, and I said goodbye to Viola and completely submerged myself as a man.

LB: How was it? It must be easier. [laughs]

VD: Oh, I loved it. But it was actually very difficult for me to do. And at the end of those two weeks, when I went back to Viola, the woman, I appreciated her more. I was saying hello to her again, and every aspect of my hair, my eyes, my nails, all the things that I probably didn’t even notice before. Even my thoughts and my feelings.

LB: Whenever I see you at awards shows, whether you are presenting or receiving an award, people stop and listen to you. That…command.

VD: Um, I don’t see the command. [laughs] Other people see it much more than I do. I will say that I think my greatest source of strength is my authenticity. If I try to channel some other being, I get lost. That’s when my anxiety level goes up. Growing up in Central Falls [R.I.] as the only kinky-haired chocolate-brown girl, I always was trying to channel the girls who had the Farrah Fawcett look. It had disastrous results. So the only thing I can do is channel my authenticity. That is really a powerful tool because we spend our entire lives trying to get there. If you are projecting that, that’s what people are attracted to.

LB: You’ve achieved your mainstream movie success as an adult. What are the benefits of success coming when you’re a grown-up?

VD: It was probably easier because I know what I want. I’ve been doing this for 33 years. I know what’s good and what’s bad. If it doesn’t shift people in some way, then it’s not a piece of art. The only way to achieve that as an actor is to study life. You can’t study another performer. What I have learned at my age is the courage to do that. How to Get Away with Murder was a perfect example. I could’ve lost 40 or 50 pounds. I could’ve worn a long, straight weave. But I decided to start with a palette that was me. Physically me. Age-wise me. My wrinkles. All of it. The fact that I had the courage to do that is a testament to how long I’ve been in the business. What I’ve seen, how often I’ve failed. How my heart has been broken time and time again.

LB: Performing is supposed to be an individualistic profession, yet there is such homogeneity in Hollywood.

VD: Here’s the issue with our business. It’s a business of deprivation. And when people are deprived, they get desperate. We are in a profession that has a 95 percent unemployment rate. And only .04 percent of actors are famous. That’s it. If you look at social media, you think, “OK, I want to make a lot of money, so I’m going to be an actor. Look at Viola, look at Reese Witherspoon, look at Kerry Washington.” People don’t realize that represents .04 percent of the profession. More than likely, if you’re going to be an actor, you’re going to take a lot of crappy roles — if you can even find the work. So when you’re desperate and you’re not working, the first thing you do is look at the people who are working and try to do what they do. That’s what all of us are trying to do in culture anyway. We are trying to find a way to fit in, to be noticed, to have a meaningful life. That’s why people try to look young, cute, thin, to have more access to money. Any kind of status symbol so they can be seen and valued. And in our profession, the race is just to work.

LB: Especially now. How did you handle the lockdown?

VD: I didn’t do well at first. I know a lot of people felt great with it. I did feel great, in terms of I don’t like working so much. Nowadays, being a woman is juggling motherhood, being a wife, cooking, and then being the CEO and knowing how to optimize your business. I don’t like working like that. It drives me completely insane. So the time off was wonderful, but I’m an empath. I don’t know how to channel the pain and suffering that other people are going through and say, “But I feel great!” It was very difficult for me to process what was happening.

LB: How are you staying the course, especially for [your 10-year-old daughter] Genesis? There are so many headwinds.

VD: In terms of Black Lives Matter, I am who I always am. What’s happening is what has always been happening. We just decided to wake up. How have I been able to process it? I have days when I fail miserably. And that’s when I need my two or three glasses of wine. But I’m trying not to lose hope in humanity. The only thing I can control in life is what I put into it. That’s the only thing I can do with Genesis. Teach her that you still have to be kind, you still have to be empathetic. That that’s going to be a part of your legacy. You have no idea whose life you can shift. And at the same time, even someone who doesn’t share your belief system could be a friend. That is the complexity of life.

LB: Understanding that is vital, especially leading up to the election.

VD: I think that [lawyer and politician] Barbara Jordan said it best. She said, “What people want is simple. They want an America as good as its promise.” And the bottom line is that it is a system that’s been built on the dehumanization of Black and brown people. Everything from Jim Crow to the Black codes to incarceration to the millions and millions of lives lost in the Middle Passage. The trauma of that still reverberates to this day, and not just with the Black and brown people, but with the so-called oppressors, who are the white people. We all have been affected by the trauma. It’s almost as if we have to relearn how to interact with each other. How to love each other. How to meet each other as equals. That’s very difficult because our caste system is about one-upmanship. An American ideology and ethos that is based on whoever is on top gets the American Dream and whoever is on the bottom, who fails the test, does not. We have to dismantle that. If we are indeed woke and do not want another 2020 or 1965 or 1877 or 1865 to happen again, then we need to slowly begin dismantling this system. And then look into reparations.

Source : InStyle